الصورة عن طريق Gianluigi Forte

I didn’t go to India to put on a Hindu costume; I got into Vedic teachings to uncover all the costumes I’d been wearing and to find out what I was at my core. The sacred literature of India explained this in a way that gave me the broadest understanding of spirituality I’d ever had. I was ready to dive into the ocean of devotion, living in India with all its colors, scents, and raw beauty.

حفظ الأشياء في منظورها

The train trip from Delhi to Kolkata was twenty-five hours. There was no air conditioning, and it was hot. I tried to keep things in perspective. This was the cheap train, costing me about eight bucks. I was accompanied by five young Indians—four monks and one shop owner, Mohan, the brother of two of the monks.

Mohan was shorter than me, dressed in a collared shirt and maroon sweater vest. He had a little mustache and short, black, sweaty hair combed over to the side. He wasn’t a monk, but he believed it all. I, on the other hand, was new to this. Still hesitant. Questioning too much.

The monks barely spoke to me—not in a rude way; they were just focused on reading or chanting on their japa mala, which are like an Indian rosary. Although I understood, this appeared a little robotic and boring.

I struggled with chanting japa, a meditative repetition of a mantra or divine name that is practiced in many Eastern spiritual traditions. Perhaps my mind was too busy. Perhaps that was a reason to take it more seriously.

If the monks were a little aloof, Mohan was the opposite. Overly engaging. Dramatic. He would get close to me and whisper, then speak loudly, waving his arms.

One of the brothers, Gopal, was the complete opposite of Mohan. He was introverted. He had little emotion and remained private.

Ready for An Adventure

I was seated in the middle of the bench with one monk on either side and two more (plus Mohan) across from me. It was tight, but I felt I could do this. Twenty-five hours. Big deal. I would sleep for eight. Read a little. Chant a little.

The squeaking of the train continued.

I noticed that some people were getting on the train and not sitting. They were just standing there. Some were even sitting on the floor near the exit doors.

“Why aren’t they sitting down in a berth like us?” I asked.

“They are very poor,” Gopal said. “They have no money to sit.”

I was appalled. “So they’re going to sit on the floor of this dirty train for twenty-four hours?”

“You are right!” he said firmly. “It is very rude of us to not invite them to sit with us.”

“No . . .” I said, backpedaling. “I wasn’t saying—”

But Gopal was already motioning to them and telling them loudly to join us in our berth. I couldn’t understand the Hindi, but it was some type of official invitation.

I tried to reason with him. “We’re already packed in here. We can’t fit any more.”

ولكن بعد فوات الأوان.

Personal Space?

What had I done? Gopal was now helping them get comfortable in the berth. I said nothing, not wanting to seem whiny. Two old ladies were encouraged to sit on either side of me, sandwiching me even more tightly. The bench that was designed for three was now holding five. This might go on for the next twenty-four hours! فكرت.

Two more new people—older men, one with a massive turban that was taking up even more space—sat across from me. Mohan was in between them, facing me, as squished as I was. I was cramped and hot. I wasn’t a happy camper.

Every culture has different ideas of personal space. In the United States, we tend to like a bit of room. But the ladies on either side of me didn’t understand my needs. They were snuggling up to me, resting their heads on my shoulders.

The monk who’d invited them to sit with us felt good about the noble act of offering the poor a bit of bench at our expense. I, on the other hand, wanted to kick his ass for not asking me if I minded having two extra bodies beside me for the next twenty-four hours. I could feel the heat of the old ladies’ bodies in the already ovenlike train. I was cracking.

I was losing it.

ركز...

Two hours passed as I did my best to focus on the monks across from me, ignoring the women suctioned onto my shoulders. Sweat dripped from my brow, burning my eyes. The old ladies were also sweating. The heat was unbearable. Thick like a blanket. If there’s a God in the sky, please help me، اعتقدت. How many more hours of this? How can it get any worse?

It could. And it did.

The train broke down in a field for what would end up being an eleven-hour delay. No air conditioning. No air to breathe.

The most fascinating thing was that nobody seemed to care—not the conductors nor the other passengers. Not the monks and not the travelers in my berth. Nobody seemed to care except me. I cared a الكثير. I lost it.

I went into blaming mode. I—a young, angry white monk—stormed around the train, searching for the conductor, or anyone in charge, and demanding accountability for the faulty system. Frustrated that nobody else was as upset as I was, I found myself saying out loud, like a mad man, “Doesn’t أي شخص have anywhere to go except me?”

When I finally realized my efforts were futile and that everyone else was accepting what they couldn’t control, I went back to my bench, squeezed into my seat, and sat down. I was defeated, but I wasn’t quite ready to learn the lesson that was right in front of me.

الدرس

Just like me, Mohan was flanked on both sides by strangers. Cramped. Hot. And for some reason, he was still wearing his sweater vest. I’m sure he’s uncomfortable, I thought. Yet I seethed with envy. Why can’t I just be tolerant like him and all these other people? Why am I so damn entitled?

Mohan had every reason to complain, but he wasn’t complaining. He was at ease. Everyone in this country seemed so much more tolerant and at peace than me.

This realization fueled self-loathing, which I promptly started projecting onto everyone else. Mohan was still bubbling with enthusiasm. Talkative. Spiritually enlivened. Bright-eyed. يبتسم. But I found myself thinking that he was جدا enthusiastic, and I was growing increasingly annoyed.

I wanted to complain and have others commiserate with me. That was my go-to attitude in tough times. But none of these people would commiserate. None of them had anything to complain about.

الانشوده

Mohan noticed my distress. He lifted his eyebrows. “Ra-aa-ay,” he said in his singsong voice, making my name into a three-syllable word. This annoyed me even more. “What’s the matter, Ra-aa-ay? You have so much knowledge, so much wisdom! You know that the material world is temporary and filled with pain. You know that we should be compassionate to all these souls.”

He pointed to my chest, voice dropping to a whisper. “You know the importance of compassion. To the degree we identify the body as the self, we will suffer.” Then he fell silent, nodding his head theatrically. A real performer.

Unfortunately, he was giving advice to a person who couldn’t hear it. I wanted to be angry and frustrated. I didn’t respond.

“Ra-aa-ay!” Mohan said, smiling. “You have knowledge about the material realm, and you have some insight into the spiritual realm.” He raised his voice so that people outside our berth could hear it. “You have a valuable gem! Live it! Give it! Look around this train, Ray!” He dropped to a whisper again. “The people are lost. Snacking. Gabbing. Sleeping. Talking nonsense. أنت have the power to inspire them. Change their hearts with transcendental sound.”

جعدت جبين. ماذا؟

He leaned closer. “You have wisdom now, Ray. You must give it. You must give this wisdom away!” His smile and gaze were increasingly intense. I thought he might burst out laughing.

“What are you talking about?” I was dumbfounded. Disturbed. Sweaty.

“We must take the sacred sound of the Hare Krishna mantra,” he bellowed, pointing his finger into the air, “and give it away freely to the entire train!”

“What?” I wanted him to keep his voice down.

“We must make the entire train chant the ماهامانترا!” He stood up, beaming.

I still had no idea what he was talking about, but I wasn’t in the mood for any of it. I glared at him, incredulous. “Do whatever you like, Mohan. Just leave me out of it.”

He accepted this and went on his mission without me. He jumped onto one of the benches, holding on to the chains that supported the luggage racks. He leaned forward into the aisle.

“Our life is short!” Mohan addressed the packed train, speaking deeply, firmly, with hope in his voice. “There is so much time wasted! Let’s not waste another moment! Let’s all take this moment to glorify the divine Lord Krishna. Let’s all invite Krishna’s sweet, sacred name onto our tongues and into our minds and hearts! Let us sing and chant!”

Mohan reached into his pocket, pulled out karatalas-small cymbals— and skipped down the aisle, playing them and chanting the Hare Krishna mantra. He looked like a child joyfully bounding through a field.

I was shocked. Not because he was dancing freely and joyously, indifferent to public opinion. No, I was shocked because people started singing along. الجميع started singing, an impromptu chorus.

By the time the old women who were pressed into me started singing, I was no longer annoyed. I was happy.

Mohan continued dancing and singing like an actor in a musical leading a chorus. The most fascinating thing of all, though, was that I started singing. I started clapping. The power of the sound and the energy coming out of little Mohan lit me up. The mantra lit me up. That sacred sound vibration designed to call divinity into our lives lit me up.

This unpretentious, five-foot-tall man, with his heart focused on God, lit up that entire train. Families were singing, the elderly were chanting, people were smiling and even dancing. He turned what could—or even should—have been a miserable experience into something I’ll never forget. That chanting lasted at least an hour. People were swept up by this mantra that they all knew.

• ماهامانترا is considered to be the most powerful of all mantras because it gives people what they need, not necessarily what they want. It’s a mantra for trusting that our lives are in divine hands. A mantra that represents connection, and that reveals that we’re part of a greater, divine plan.

On that train trip, it was delivered with humility, enthusiasm, and joy at the perfect moment. It jolted everyone on that train out of their minds, their thoughts, their gossip, and the minutiae of their existence.

It shook me, slapped me, and embraced me. It got me out of my complaining. My pity festival. My self-hatred and my bitterness.

الدرس المستفاد

I learned a great lesson that day. The sounds that are in your mind and flow out of your mouth will make you joyous or miserable. I was letting the negative sounds of my mind own me. Mohan changed all that with a mantra.

I learned not just tolerance or acceptance for what I couldn’t control; I learned that this mantra, delivered with the right attitude, brought joy.

One person with a good attitude can change many. I was changed that day. I still am.

“The majority of my problems,” I wrote in my journal that day, “don’t come from anything external. Not the weather, not the government, not mistreatment, and not lack of resources. The majority of my problems are coming from my bad attitude. I need to be careful what I consume through my ears. After all, the sounds I put in become the sounds in my mind, which become the sounds flowing out of my mouth. All these sounds are creating me, for better or for worse.”

حقوق التأليف والنشر 2024. كل الحقوق محفوظة.

مقتبس بإذن.

المادة المصدر:

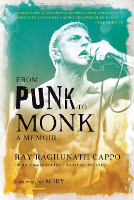

كتاب: From Punk to Monk

From Punk to Monk: A Memoir

by Ray "Raghunath" Cappo.

The heartfelt memoir of Ray Raghunath Cappo, a legendary hardcore punk musician-turned-monk—and pioneer of the straight-edge movement—told with warmth, candor, and humor. This heartfelt memoir chronicles Ray’s emotional and spiritual journey from punk to monk and beyond.

The heartfelt memoir of Ray Raghunath Cappo, a legendary hardcore punk musician-turned-monk—and pioneer of the straight-edge movement—told with warmth, candor, and humor. This heartfelt memoir chronicles Ray’s emotional and spiritual journey from punk to monk and beyond.

لمزيد من المعلومات و/أو لطلب هذا الكتاب بغلاف مقوى، انقر هنا. متوفر أيضًا كإصدار Kindle.

عن المؤلف

قم بزيارة موقع المؤلف على الرابط التالي: Raghunath.yoga/

As a teen in the 80s, Ray Cappo founded the hardcore punk band Youth of Today, which championed the principles of clean living, vegetarianism, and self-control. After experiencing a spiritual awakening in India, he formed a new band, Shelter, devoted to spreading a message of hope through spiritual connection. Ray currently leads yoga retreats, trainings, and kirtans at his Supersoul Farm retreat center in Upstate New York, as well as annual pilgrimages to India. He is the co-founder and co-host of

As a teen in the 80s, Ray Cappo founded the hardcore punk band Youth of Today, which championed the principles of clean living, vegetarianism, and self-control. After experiencing a spiritual awakening in India, he formed a new band, Shelter, devoted to spreading a message of hope through spiritual connection. Ray currently leads yoga retreats, trainings, and kirtans at his Supersoul Farm retreat center in Upstate New York, as well as annual pilgrimages to India. He is the co-founder and co-host of